By Ziad Abdel Samad and Bihter Moschini, Arab NGO Network for Development (ANND)

In 2015, with the adoption of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), governments acknowledged the mutually enforcing power of peace and development. The 2030 Agenda represents a paradigm shift in terms of universality and interlinked goals, including across borders and affirms the need for a rights-based approach to peace and security, one focused on prevention. At the same time, most governments are still producing, trading and spending more on arms, thereby fueling a militarized approach to peace and security. Dominant power talks on how to achieve peace continue to silence those impacted most by conflicts and wars, including women and children. Profits made under war economies and through the arms trade continue to deepen inequalities and violate the rights of those with enormous humanitarian and development needs.

Instabilities, conflicts and wars are ‘sustained’ in many parts of the world, for the sake of security and the narrow interests of those who benefit from them, moving in a direction opposite to the goal of ‘leaving no one behind’. Long-term solutions for achieving peace and stability require more than a mere commitment to SDG 16 on peaceful and inclusive societies; they require revising policies at all levels (economic, political, social, cultural…etc.) and adopting inclusive and comprehensive development plans.

Achieving sustainable development and sustainable peace are the two sides of the same coin, representing the two pillars of the UN system. “No peace, no development”, “no peace, no justice” and “no development, no security” are commonly used slogans that illustrate the impossibility of separating one from the other.

In 2015, with the 2030 Agenda focusing on peace, justice, effective and accountable institutions, as well as inclusive societies, the international community acknowledged once again that peace is prerequisite for sustainable development. Likewise, within the United Nations system the UN Secretary-General introduced a restructuring of the peace and security pillar. [fn] UN Secretary General (2018). [/fn] This outlined a more holistic and comprehensive approach to peacebuilding and sustaining peace, making the linkages to economic and social development and the promotion and protection of human rights.

The Secretary-General’s report also acknowledged the need for cross-pillar work, at national and regional levels and across policy processes. On 27 April 2016, the General Assembly and the Security Council adopted substantively identical resolutions on peacebuilding, [fn] A/RES/70/262 and S/RES/2282 (2016), respectively. [/fn] concluding the 2015 review of the UN Peacebuilding Architecture. In those resolutions, both the General Assembly and the Security Council identify sustaining peace as:

a goal and a process to build a common vision of a society, ensuring that the needs of all segments of the population are taken into account, which encompasses activities aimed at preventing the outbreak, escalation, continuation and recurrence of conflict, addressing root causes, assisting parties to conflict to end hostilities, ensuring national reconciliation, and moving towards recovery, reconstruction and development, and emphasizing that sustaining peace is a shared task and responsibility that needs to be fulfilled by the Government and all other national stakeholders, and should flow through all three pillars of the United Nations engagement at all stages of conflict, and in all its dimensions, and needs sustained international attention and assistance.

A High-Level UN General Assembly debate on peacebuilding and sustaining peace in April 2018 welcomed a renewed emphasis on conflict prevention. [fn] See: www.un.org/pga/72/event-latest/sustaining-peace/. [/fn] It addressed the root causes of conflicts, strengthening policy coherence, funding for peacebuilding operations, strengthening partnerships at various levels, and engaging women and youth both in conflict prevention and peacebuilding efforts. [fn] See: www.un.org/pga/72/wp-content/uploads/sites/51/2018/04/HLM-on-SP-2-April.pdf [/fn] The representative from Mexico, speaking on behalf of the Group of Friends of Sustaining Peace, said: “we have come a long way in the pursuit of a more inclusive and integrated approach to sustaining peace and addressing the root causes of conflict, instead of just responding to crises.” Echoing this, the Liberian representative said that countries should use their collective ingenuity and resources to invest in prevention and eliminate the main drivers of conflict, particularly at a time of declining funds for such activities. “Imagine”, he said, if “rather than investing in bullets and tanks, we could have them invest in roads and energy, hospitals and schools.” He added: “Pursuing the path of preventing conflict and sustaining peace gives us a real chance to lift our humanity and bend the present trajectory of fear and war.”

The President of the UN General Assembly reinforced the gains from sustaining peace, citing a recent World Bank-UN report that for every US$ 1 spent on prevention up to US$ 7 could be saved – over the longer term. [fn] UN/World Bank (2018), p. 2. [/fn]

Yet there is a long way to go on challenges and implementation, particularly with increasing concerns over violent extremism. Several studies suggest that investing around US$ 2 billion in prevention can generate net savings of US$ 33 billion per year from averted conflict. [fn] UN/World Bank (2018), pp. 4-5. [/fn] Similarly, while achieving peace and stability is the ultimate aim for many, policies for sustaining peace, by addressing the root causes of conflicts and wars remain limited. Therefore, the following steps are necessary to address these challenges:

1. Shift from militarized security and budgets to rights-based sustainable development and public sector budgets

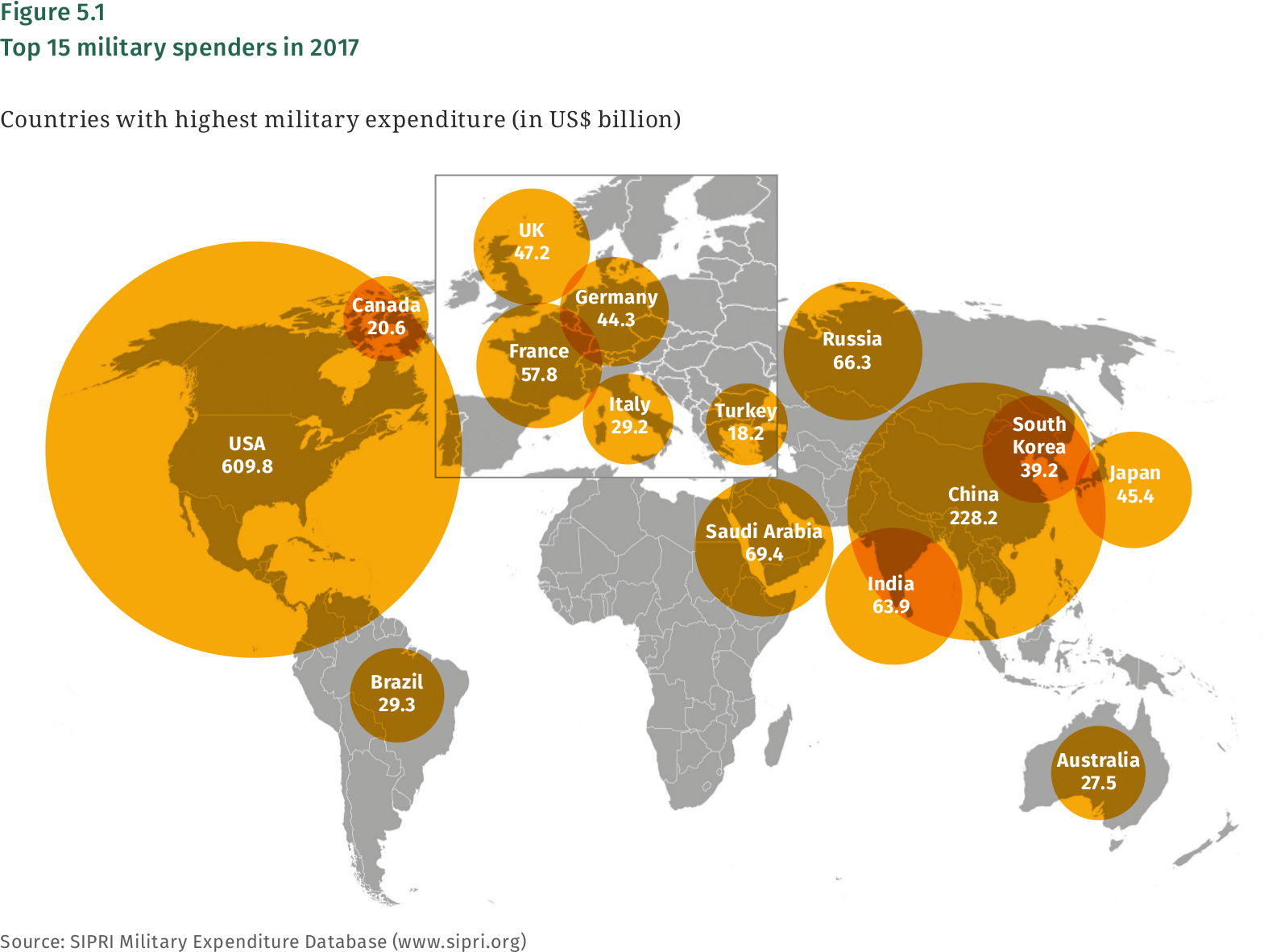

The first aspect of sustaining peace requires a paradigm shift from a state security approach towards a focus on human security and rights-based budgeting, doing away with military-prioritized budgeting. The sad reality shows that “the world is over-armed while peace is under-funded”. [fn] The statement by the Global Campaign on Military Spending (http://demilitarize.org/). [/fn] The global trends reflect that military spending is increasing worldwide. Global military spending in 2017 was US$ 1.7 trillion, 2.2 percent of global GDP. [fn] See: www.sipri.org/media/press-release/2018/global-military-spending-remains-high-17-trillion. [/fn] The USA continues to have by far the highest military expenditures in the world. In 2017, the USA spent more on its military than the next seven highest-spending countries combined (see Figure 5.1).

Moreover, military expenditure as a share of GDP was highest in the Middle East, particularly Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Turkey, at 5.2 percent in 2017. [fn] Ibid. [/fn]

Governments’ allocation of resources to military spending – including the selling and purchasing of arms – rather than fulfilling their obligation to use the maximum available resources for the progressive realization of economic and social rights – remain at the centre of widening and deepening inequalities, thus a core challenge to achieving sustainable development, in all countries. An analysis by SIPRI concludes that with around 10 percent reallocation of military spending to the achievement of the SDGs, major progress could be achieved, provided that the reallocated funds are effectively channeled to implement the SDGs with a comprehensive rights-based approach. [fn] Perlo-Freeman (2016). [/fn] In contrast, at the NATO Summit in Wales in September 2014, NATO members committed to increase their military spending to at least 2 percent of GDP, for the sake of the principle of ‘collective defense’. In follow up, US President Donald Trump continuously raised the issue that most of NATO allies do not meet this benchmark, [fn] See for instance De Luce/Gramer/Tamkin (2018). [/fn] while NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg emphasized the “progress”’ and noted that the increase in military spending indicating the “right direction.” [fn] Banks (2017). [/fn]

However, more spending on defense induces less resources for sustainable development and thus has negative consequences for sustaining peace. Moreover, more ‘securitization’ of the political discourse and international relations, including the focus on cyberwarfare, become a threat to peace (see Chapter 3: Vector of Hope, Source of Fear in this report). Instead, the transformative aspirations of the 2030 Agenda ought to lead to a shift towards the demilitarization of public budgets and the allocation of the additional resources to addressing inequalities, poverty and other development challenges.

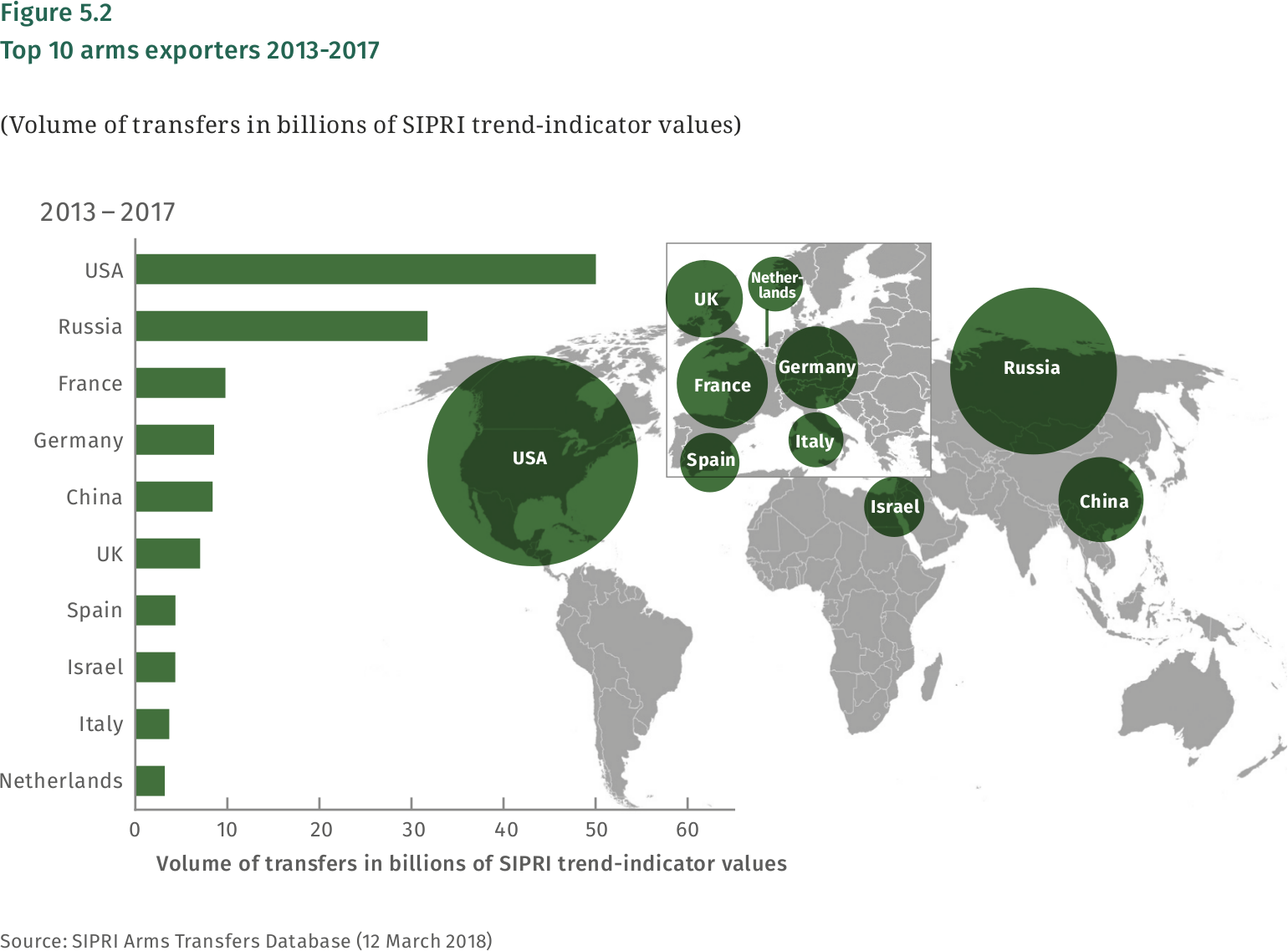

In this regard, there is an urgent need to address as well the increasing international arms trade as a main obstacle to sustaining peace (see Figure 5.2). The arms industry is considered a highly profitable sector – but only for those who produce and sell arms, at the expense of hampering peace, contributing to human rights violations, and exacerbating insecurity and instability.

This dichotomy can be seen, for instance, in European external policies: On the one hand EU member states focus on the need for security and stability within what is defined within the EU development cooperation framework as the Southern Neighbourhood region, consisting of 10 Arab States, while on the other hand the same EU countries are among the major arms suppliers to the region, together with the USA, Russia and China. [fn] French arms sales increased to Egypt and Qatar in 2015 for example, with a 67.5% surge in arms sales by the Dassault Aviation Group (www.sipri.org/media/press-release/2016/global-arms-industry-usa-remains-dominant). [/fn] Overall, arms imports by the Arab region increased to 32 percent of global arms imports in 2013–2017. [fn] See: www.sipri.org/news/press-release/2018/asia-and-middle-east-lead-rising-trend-arms-imports-us-export…. [/fn] Access to arms plays a crucial role in sustaining wars, and in contexts where instability is sustained, repression and exclusion are systematic, and conflicts are fueled; and with the ongoing arms trade, criminal economies also flourish more easily. Samir Aita reports, for instance, that in Syria, “the new trade networks have developed their activities in the chaos of war towards criminal economy, such as the production of the Captagon drug. Syria has become a major drug producer in the Middle East, and it is expected that if such criminal activities continue to develop it shall a threshold where this criminal activity should constitute the main economic resource of the country, sustaining like in Afghanistan, war on the long term.” [fn] Aita (2017). [/fn]

The production, mobilization and allocation of economic resources to militarization and securitization enable profits to enable the functioning of warlords in war economies, and exacerbate gross human rights violations for many civilians.

2. Support inclusive peace processes

The second aspect of sustaining peace is the approach adopted for conflict resolution, focused on countering violence, extremism and peacebuilding initiatives. Human rights norms should be well integrated into each of these, such as by empowering women to take pro-active roles, considering that militarization policies are most often male-dominated, silencing gender concerns while the consequences of wars and conflicts are felt harder by women and children. In order to be sustainable, peace processes should go hand in hand with revising policies at economic, social, cultural and political levels, adopting gender and human-rights-based approaches. Yet UN Women statistics show the following gap; from 1992 to 2011 only 9 percent of negotiators at peace tables were women. [fn] UN Women (2018). [/fn] The same facts and figures reveal that “when women are included in peace processes there is a 20 percent increase in the probability of an agreement lasting at least 2 years, and a 35 percent increase in the probability of an agreement lasting at least 15 years”. [fn] Ibid. [/fn]

Peacebuilding initiatives should also ensure national ownership, enhanced inclusivity and should be designed and implemented based on the specific needs of the country.

Like peacebuilding initiatives, countering violent extremism (CVE) initiatives have been directed towards the Arab region, particularly in response to the rise of violent extremists groups like ISIS. For instance by late 2017, the European Union allocated € 17.5 million to address the terrorist threat in the Arab region under its Instrument contributing to Stability and Peace (IcSP).The programme foresees strengthening the capacity of State actors that play a key role in countering terrorism and violent extremism and focuses on partnerships between authorities, youth and communities to address underlying factors that can make communities vulnerable to violent extremism. [fn] See: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-17-3225_en.htm. [/fn]

There is no doubt that violent extremism in the region, now crossing national and regional borders, has become a global threat and should be addressed. Yet the impact of CVE measures if not well designed, and if they do not incorporate human rights will remain limited. As put-forward by Saferworld, “CVE efforts can’t work if they merely go alongside problematic military and rule of law approaches. CVE will only work if it actually stands to change the tactics used by military and criminal justice actors.” [fn] Attree (2018). [/fn] This would require the adoption of a comprehensive human security approach that goes beyond the rule of law, which can be less than inclusive, and integrating economic, environmental, food, health and other components of human security. In many cases, such as Syria or Iraq, the lack of human security allows an enabling environment for violent extremism as a tool to radicalize and recruit new extremists. This clearly shows the need for more inter-linkages between inclusive development efforts and the CVE efforts. Likewise, the impacts of the arms trade have to be considered, as the availability of arms contributes to the strengthening of violent extremists groups and undermines the capacity of State actors.

3. Localize humanitarian support and implement development effectiveness principles

Once arms spending and militarized security are on the rise, conflicts and wars last longer, peacebuilding initiatives remain limited and in parallel, humanitarian assistance needs to remain constant. In 2016, around 164.2 million people in 47 countries were in need of international humanitarian assistance, affected from multiple crisis. [fn] Development Initiatives (2017). [/fn] The Top Five countries receiving this assistance are from the Arab region: Syria is number one, followed by Yemen, Jordan, South Sudan and Iraq. Total humanitarian assistance (including from governments, EU institutions and private actors) increased between 2012 and 2016 from US$ 16.1 billion to US$ 27.3 billion. [fn] Ibid. [/fn]

Despite increased assistance, the humanitarian needs will not be necessarily met unless the root causes of the conflicts have been addressed. However, humanitarian assistance can play a crucial role when it is effective and efficient: when it aims at empowering national institutions, regional and local authorities and actors, ensures localization and establishes direct linkages with long-term sustainable development needs. The increasing focus on putting resilience-building at the centre of humanitarian assistance risks shifting attention to short-term basic needs and support rather than addressing the root causes of the crisis.

In addition, complementary to humanitarian assistance is the provision of protection, particularly legal protection, for those people in need. In the Arab region this refers for instance to the huge number of Syrian refugees in neighbouring countries. Given the length of the crisis, long-term and sustainable protection measures should be designed for them; acknowledging the fact that stability and security and refugee protection are interlinked. [fn] Ghali (2017). [/fn] Residency, mobility, employment and livelihood rights for these vulnerable groups must be addressed as priorities.

Important initiatives in this respect are the Agenda for Humanity, which includes five major action areas and 24 key transformations that are needed to address and reduce humanitarian need, risk and vulnerability, [fn] See: www.agendaforhumanity.org/. [/fn] and the Grand Bargain, an agreement between more than 30 of the biggest donors and aid providers to providing 25 percent of global humanitarian funding to local and national responders by 2020, along with more un-earmarked money, and increased multi-year funding to ensure greater predictability and continuity in humanitarian response, among other commitments. [fn] See: www.agendaforhumanity.org/initiatives/3861. [/fn] These initiatives should be enhanced, implemented and monitored closely.

From responsibility to protect to responsibility to prevent?

The international community has long debated how to address serious human rights violations and worked within the international human rights law and humanitarian law framework to find answers. While it was agreed that the protection of human rights is the State’s primary responsibility, it became clear that more was needed in the face of massive human rights violations, including those in which the State itself is the major perpetrator. As a result of the debate about State sovereignty and humanitarian interventions, the concept of the responsibility to protect (R2P) emerged in 2001. However, considering the R2P principle as an international security and human rights norm, has been highly problematic, due to double standards in its implementation and the immobility of the international community in the face of its unilateral application. [fn] Nuruzzaman (2013). [/fn] The Iraqi occupation became the first case study, which showed that the unilateral application of the R2P principle brought long-term and multi-level problems for the society. The inadequacy of the R2P principle was demonstrated again in the cases of Libya and Syria, where the international community is still unable to bring about peace. [fn] Pingeot/Obenland (2014). [/fn]

Given the devastating impacts of the wars that extend across national and regional borders, the failures and limits of the normative framework should be addressed.

Indeed, accountability is a core component of sustaining peace. Its integration into the targets and indicator framework of SDG 16, on peaceful and inclusive societies and accountable and inclusive institutions, is another positive step, yet it is not enough. Moving from the R2P doctrine to the universal commitment to sustaining peace within the 2030 Agenda, there is a tremendous need for policies addressing the flaws in the global system for addressing peace and security, including the lack of democratic participation in decision-making mechanisms, in order to avoid bias and double standards. The ability to address the root causes of conflicts and wars and the move towards peacebuilding and the empowering of peaceful societies should be enhanced.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the quest for sustaining peace is highly challenged by diverse factors, as is the achievement of sustainable development. While SDG 16 should be transformative and an enabling goal for implementing the 2030 Agenda and all of its SDGs, the dynamics created by militarization, the rise in military expenditures and arms exports, the securitization of aid, based on national or international security imperatives, together with lack of commitment to development effectiveness and the urgent need for localization of humanitarian aid should be considered key issues to be addressed for its effective implementation. As the President of the General Assembly noted for the High-level Meeting on Peacebuilding and Sustaining Peace in April 2018:

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development also acknowledges the interdependence between development and peace and security. It further recognizes that ‘there can be no sustainable development without peace and no peace without sustainable development’.... The 2030 Agenda is the paramount goal of the United Nations, and it also happens to be the best defence against the risks of violent conflict. [fn] See: www.un.org/pga/72/wp-content/uploads/sites/51/2018/04/HLM-on-SP-2-April.pdf. [/fn]

Ziad Abdel Samad is Executive Director and Bihter Moschini is Programme Officer with the Arab NGO Network for Development (ANND).

Aita, Samir (2017): War Economy in the Syrian Chaos… How inter-cities and foreign trade fuel the war?

www.researchgate.net/publication/317035808_War_Economy_in_the_Syrian_Chaos_How_inter-cities_and_for…

Attree, Larry (2018): Shouldn't YOU be Countering Violent Extremism? London: Saferworld.

https://saferworld-indepth.squarespace.com/

Banks, Martin: (2017): Defense spending increased 'significantly' among NATO allies. In: Defense News, 30 June 2017.

www.defensenews.com/global/europe/2017/06/30/defense-spending-increased-significantly-among-nato-al…

De Luce, Dan/Gramer, Robbie/Tamkin, Emily (2018): Trump’s Shadow Hangs Over NATO. In: Foreign Policy, 29 January 2018.

http://foreignpolicy.com/2018/01/29/trumps-shadow-hangs-over-nato-transatlantic-alliance-europe-def…

Development Initiatives (2017): Global humanitarian assistance report 2017. Bristol.

http://devinit.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/GHA-Report-2017-Full-report.pdf

Ghali, George (2017): The Head Out of the Sand – Addressing the legal and practical options for better management of the refugee crisis in Lebanon. Beirut: Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung (KAS)/Middle East Institute for Research and Strategic Studies (MEIRSS) (MEIRSS Policy Paper No. 1, December 2017).

http://meirss.org/head-sand-addressing-legal-practical-options/

Nuruzzaman, Mohammed (2013): The “Responsibility to Protect” Doctrine: Revived in Libya, Buried in Syria. In: Insight Turkey 15:2.

www.insightturkey.com/commentaries/the-responsibility-to-protect-doctrine-revived-in-libya-buried-i…

Pingeot, Lou/Obenland, Wolfgang (2014): In Whose Name? A critical view on the Responsibility to Protect. New York: Global Policy Forum and Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung.

www.globalpolicy.org/images/pdfs/images/pdfs/In_whose_name_web.pdf

Perlo-Freeman, Sam (2016): The opportunity cost of world military spending. Stockholm: SIPRI.

www.sipri.org/commentary/blog/2016/opportunity-cost-world-military-spending

UN/World Bank (2018): Pathways for Peace: Inclusive Approaches to Preventing Violent Conflict. Washington, DC: World Bank.

http://hdl.handle.net/10986/28337

UN Secretary-General (2017): Implementing the Responsibility to Protect: Accountability for Prevention. Report of the UN Secretary-General. New York: UN (A/71/1016 and S/2017/556).

http://undocs.org/a/72/707

UN Secretary-General (2018): Peacebuilding and sustaining peace. Report of the UN Secretary-General. New York: UN (A/72/707 and S/2018/43).

www.un.org/en/peacebuilding/pbso/pdf/SG%20report%20on%20peacebuilding%20and%20sustaining%20peace.As…

UN Women (2018): Facts and figures: Peace and security. New York.

www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/peace-and-security/facts-and-figures#notes