By Barbara Adams, Global Policy Forum

In the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, UN Member States pronounced their commitment to “reaching the furthest behind first”. What does it mean to apply this commitment to governance and related policies, budgets and institutions?

This chapter explores the implications for global governance of the promises of the 2030 Agenda, the practice of the High-level Political Forum (HLPF) and the many and sometimes contradictory approaches and initiatives of the UN system and its ‘governors’.

It highlights the need to move from the current pay-to-play orientation to one of democratic accountability for ‘people and planet’ and recommends a strengthened and re-positioned HLPF and UN General Assembly to drive momentum for a UN as the leader of rights-based multilateralism.

1. HLPF – modelling a new generation of global governance

The High-level Political Forum (HLPF) for monitoring the 2030 Agenda on Sustainable Development was mandated by the 2012 UN Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio+20), and the details were negotiated by Member States in 2013. Proposals for a robust accountability body were blocked mainly by three States and the outcome was a forum/talk shop, removing the accountability voice in favour of follow-up and review.

While honouring the Rio+20 agreement that it would be universal and high-level, the HLPF started its life lacking an official identity (UN document number) and with fewer working days and a smaller UN budget allocation than the Commission on Sustainable Development, the body it replaced.

This was clearly an attempt by a few States to minimize and ‘invisibilize’ the HLPF agenda, particularly with regard to monitoring and accountability.

Despite this, the HLPF has become the go-to forum for the last four years. It has a global constituency among Member States, UN agencies, civil society and the private sector. Member States have taken ownership of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and many have integrated them into their national planning and budgets. The up-take among countries has broken the mold of the programme country/donors relationship that prevails elsewhere in the UN system.

So many countries have volunteered to report on their progress through the Voluntary National Reviews (VNRs) at the annual HLPF session (some for the second and even third time) that the session is staggering under the weight of not enough time – and not enough substance, too much talk and not enough (inter)action.

With one third of the SDG implementation period to 2030 already over, 2019 is the time for serious ‘lessons learned’ from this first phase. The final decade must build on the evident and abundant interest, to inject urgency, action and accountability.

The next phase should bring the HLPF away from the ECOSOC orbit and the scramble of UN agencies to stake a claim to specific goals. The SDG Summit in September 2019 and the HLPF review process to take place in 2019-2020 are opportunities to reposition the HLPF more firmly in the General Assembly machinery, similar to the direction taken by the Member States for the Human Rights Council (HRC) and the Peacebuilding Commission (PBC) in 2005. With an agenda of equal importance and intimately connected to those of the HRC and PBC, the General Assembly should establish a third such body, a Sustainable Development Council supported with complementary machinery at regional and thematic levels. Furthermore it should convene, on a regular basis, inter-council/commission meetings. As part of broader UN reform efforts these councils could refresh (and replace) much of the work of the General Assembly Second and Third Committees, which includes economic and social development, gender equality and human rights.

While the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs have propelled the drive to break out of the siloes of thinking and programming, this has not been matched at the governance level, with disproportionate focus on a single body. The HLPF as currently configured is only a global forum and the review process threatens to go no further than tinkering with working methods. The need for integration, prevention and addressing root causes in policy-making demands a new role for the UN General Assembly, that of adjudicator across policies, across sectors and across institutions. The SDGs, collectively and by design, embody cross-cutting, cross-border and intersecting policy demands.

The growing tensions between trade and investment regimes and human rights obligations, between tax avoidance and illicit financial flows and the vital role of public finance throw into sharp relief massive governance failures at the national and global levels. Trade-offs between policies and across borders cannot continue to be ignored. The UN’s highest political body needs to exert leadership and position itself as the cross-cutting governance space.

The General Assembly would also benefit from reconfigured Member State representation (the prerogative of each Member State to decide) to close the gap between global presence and country priorities and plans. Representatives in global arenas and delegates to intergovernmental processes should be drawn not only from the executive branch but also from the legislature and sub-national bodies. This is essential to put the brakes on the trend towards replacing democratically accountable country representation with ‘stakeholders’ and legislation and regulation with partnerships. Such representation will also contribute to transparency and coherence across line ministries and enhance country ownership.

In establishing the HLPF, the Rio+20 conference mandated that it be held at Summit level every four years. In 2019 this will take place in September in conjunction with the annual UN General Assembly high-level debate. This is inadequate to the task; rather, it should follow the pattern of other UN major bodies that convene for a two to three-day conference every four or five years (such as the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), or the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty), not a day tagged on in September for speeches. Furthermore, summit leadership should be charged not to reflect and put a stamp on earlier meetings and declarations, but to drive the agenda forward, flag major concerns and emerging issues, and kick-start related action plans.

The first phase of SDG monitoring has concentrated on quantity – of countries reporting, on processes and institutions and constituencies hitching their flags and futures to the 2030 Agenda. The second phase must show quality as well as seriousness in addressing the obstacles to achieving the SDGs. It must break the ’domestication only’ approach currently dominating the country reporting in the VNRs and address the trade-offs across goals and spill-over effects across borders. Many goals cannot be achieved in country isolation, but are dependent on international cooperation. There are enormous differences among countries and governments in their policy space to influence and shape global regimes and rules. A new reporting framework needs to be developed to measure the power imbalances and be an obligatory chapter in VNR reporting.

The 2019 Global Sustainable Development Report (GSDR) by the Independent Group of Scientists could show the way, as it seeks to operationalize a truly integrated approach, especially across ministry mandates and borders. In previewing the report, the group’s co-chair explained:

We have significant trade-offs between some of these SDGs and that means if you purely pursue one SDG you will have unintended side effects, which hurts progress overall …. We can only achieve SDGs if we simultaneously look across transnational boundaries. [fn] Extract from briefing on the 2019 Global Sustainable Development Report, 13 April 2019. [/fn]

The Global Report’s attention to synergies, trade-offs and unintended consequences should be incorporated into global reporting requirements for the VNRs, along with States’ extraterritorial obligations (ETOs). Regional processes are platforms for States to report on their progress and priorities and country processes should contribute to the awareness, commitment and ownership needed to achieve the SDGs. While UN agencies can assist this process, they cannot and should not substitute for it. Country processes should engage the different sectors of society, and be led by the legislative not the executive branch of government.

For the HLPF, as for other UN governance forums, Member States face the challenge of shifting gears from tinkering to transformative change.

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development- a game changer for the UN?

The adoption of the 2030 Agenda has prised open the lid on many stubbornly resistant dynamics and approaches prevalent in the UN system and its inter-governmental processes. It has been a major driver for reform efforts and spurred attention to strengthening the science-policy interface and deepening capacity for data collection and analysis.

The 2030 Agenda has been in many ways a game changer. Its universal application requires all countries to report on their progress in achieving the SDGs, not only programme countries or development assistance recipients. It has also driven long-overdue UN development system reform and given impetus to the need to address root causes in the pursuit of sustainable development and sustainable peace.

UN human rights experts have offered high-quality analyses and recommendations to reach the vision of 2030. The human rights machinery demonstrates a comprehensive set of quality standards, from poverty elimination to housing, water and sanitation to debt and trade agreements. These are available to all Member States and their residents, although they are severely underutilized.

Civil society organizations (CSOs) have maintained the commitment many demonstrated during the drafting of the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs into monitoring and contributing to their implementation. Throughout, they have shown an impressive range of self-organizing and diverse ways of working from community to global level, often demonstrating a unique blend of experience and expertise.

Their autonomy is recognized by the rights of participation spelled out in the HLPF resolution, which set the minimum standard for the UN as a whole including the General Assembly. [fn] UN General Assembly (2013). [/fn]

The challenge of the 2030 Agenda has been taken up across the UN expert bodies including the Committee of Experts on Public Administration (CEPA). Addressing the need for effective, accountable and inclusive institutions, CEPA elaborated a set of governance principles regarding effectiveness, accountability and inclusiveness which were adopted by Member States in 2018 (see Box I.1 for a selection). [fn] Economic and Social Council resolution E/RES/2018/12 of 20 July 2018 (https://undocs.org/E/RES/2018/12). [/fn]

Box I.1: CEPA Governance Principles

|

Effectiveness

|

Inclusiveness

|

|

Accountability

|

|

Source: UN Doc. E/2018/44 (https://undocs.org/E/2018/44), pp. 17ff.

Implementation gaps – accountability failures

The SDG implementation phase since 2016 has certainly spun off many initiatives, studies, meetings and reports. At the HLPF alone there have been a total of 158 VNRs over four years. The UN’s Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA) administers a platform for partnerships that currently hosts 4,361 “partnerships/commitments” and there are frequent business and investor events co-organized or facilitated by UN agencies and programmes. [fn] The “Partnerships for SDGs online platform”: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/partnerships/ (as of 12 May 2019). [/fn] The international financial institutions (IFIs) and multilateral development banks have all called for moving from billions to trillions.

While the UN ‘family’ has embraced the profile of the SDGs and is campaigning to increase awareness of these at all levels, critics express concern that much has been characterized by cherry picking, self-promotion and self-positioning, apparent in abundance from all players – governments, UN agencies, corporations and CSOs alike.

All players are understandably presenting themselves as committed to and vital for the achievement of the SDGs. But presence, persuasion and numbers are still the limited and inadequate currency for measuring impact.

The remaining decade to 2030 needs to build in cycles of quality and independent oversight, and robust accountability. This will require a dramatic shift from the win-win, pay-to-play dynamic prevalent around the UN.

A first step would be to incorporate benchmarks, not only indicators but also actions, to delineate SDG-washing by governments and corporations that highlight best practices while hiding domestic and extraterritorial impacts such as emissions and pollution, lack of labour standards and so on. To overcome piecemeal and inadequate responses and support genuinely transformative actions, not only is a change of mindset essential, but also of financing strategies, of measurement, of incentives and of reporting and monitoring by public institutions, including the UN. These must highlight obstacles to achieving the SDGs with the same attention as actions to advance them.

The HLPF as currently set up and practicing cannot do this. It is a platform that welcomes all and challenges none.

2. A new generation of global governance – where does the UN fit in?

According to the Secretary-General, the 2030 Agenda is “an agenda aiming at not leaving anyone behind, eradicating poverty and creating conditions for people to trust again in not only political systems but also in multilateral forms of governance and in international organizations like the UN”. In 2019 he stated:

I think it is important to recognize that there is a paradox because problems are more and more global, challenges are more and more global, there is no way any country can solve them by itself, and so we need global answers and we need multilateral governance forms, and we need to be able to overcome this deficit of trust, and that in my opinion is the enormous potential of the 2030 Agenda. [fn] UN Secretary-General (2017). [/fn]

The Secretary-General sounded the alarm in his opening statement for 2019:

As we look ahead to 2019, I won’t mince words. Alarm bells are still ringing.

We face a world of trouble. Armed conflict threatens millions and forced displacement is at record levels. Poverty is far from eradicated and hunger is growing again. Inequality keeps rising. And the climate crisis is wreaking havoc. We also see growing disputes over trade, sky-high debt, threats to the rule of law and human rights, shrinking space for civil society and attacks to media freedoms.

These ills have profound impacts on people’s daily lives. And they are deeply corrosive.

They generate anxiety and they breed mistrust. They polarize societies – politically and socially. They make people and countries fear they are being left behind as progress seems to benefit only the fortunate few.

In such a context, it is not difficult to understand why many people are losing faith in political establishments, doubting whether national governments care about them and questioning the value of international organizations.

Let’s be clear: the lack of faith also applies to the United Nations.” [fn] UN Secretary-General (2019b). [/fn]

The three pillars of the UN cover the full breadth of the challenges and have been evolving beyond their initial framing to maintain their relevance to today’s and emerging challenges. The question is whether this revitalization and related UN reforms are only “catch-up” or can be transformative and accountable to SDGs.

All too often the way forward is reduced to the oft-repeated irony of how the United Nations is held in low esteem at the very time it is needed the most.

And a cursory reality check is sobering

The human rights work of the UN receives a scant 3.7 percent of the total UN regular budget; [fn] OHCHR regular budget appropriation in 2018-2019, https://www.ohchr.org/EN/AboutUs/Pages/FundingBudget.aspx. [/fn] and the Office of the High Commission for Human Rights (OHCHR) has a total of 558 regular staff members that constitute 1.2 percent of the total UN staff of 44,000 and have struggled to be heard at country and global levels. [fn] See https://careers.un.org/lbw/home.aspx?viewtype=VD. [/fn]

The UN development system (UNDS)’s welcome emphasis on the country level risks under-estimating external constraints and under–utilizing its own human rights standards. Over decades it has neglected attention to the impact of global regimes on national policy space and country ownership; for example, emphasizing domestic resource mobilization while ignoring illicit financial flows. The UNDS reforms underway aim to correct this: “Countries need high-quality and integrated policy support, a better articulation of our normative and operational assets, stronger cross-border analysis, disaggregated and reliable data for informed decision-making.” [fn] UN Secretary-General (2019a). [/fn] However, dynamic reform is being held back by the failure of a few major donors to endorse the Secretary-General’s proposal for assessed funding needed to jump-start implementation.

The peace and security pillar of the UN demonstrates greater understanding that security is internal (inequalities, gender discrimination, human rights, decent work) as well as cross border and not only in traditional ways (most evidently in impact of climate change, financial contagion, and migration). However the primary governance body, the Security Council, lacks credibility and is dominated by the five veto-wielding permanent members (P5), all among the top six arms exporters worldwide. [fn] See: https://www.sipri.org/yearbook/2018/05 [/fn]

The governance reach of the Security Council and the P5 extends well beyond the peace and security mandate of the Security Council: explicitly as a gatekeepers for other mandates, including of the International Criminal Court and the Peacebuilding Commission; implicitly as the P5 leverage their influence as the major donors across the UN system.

Relationship between governance and funding

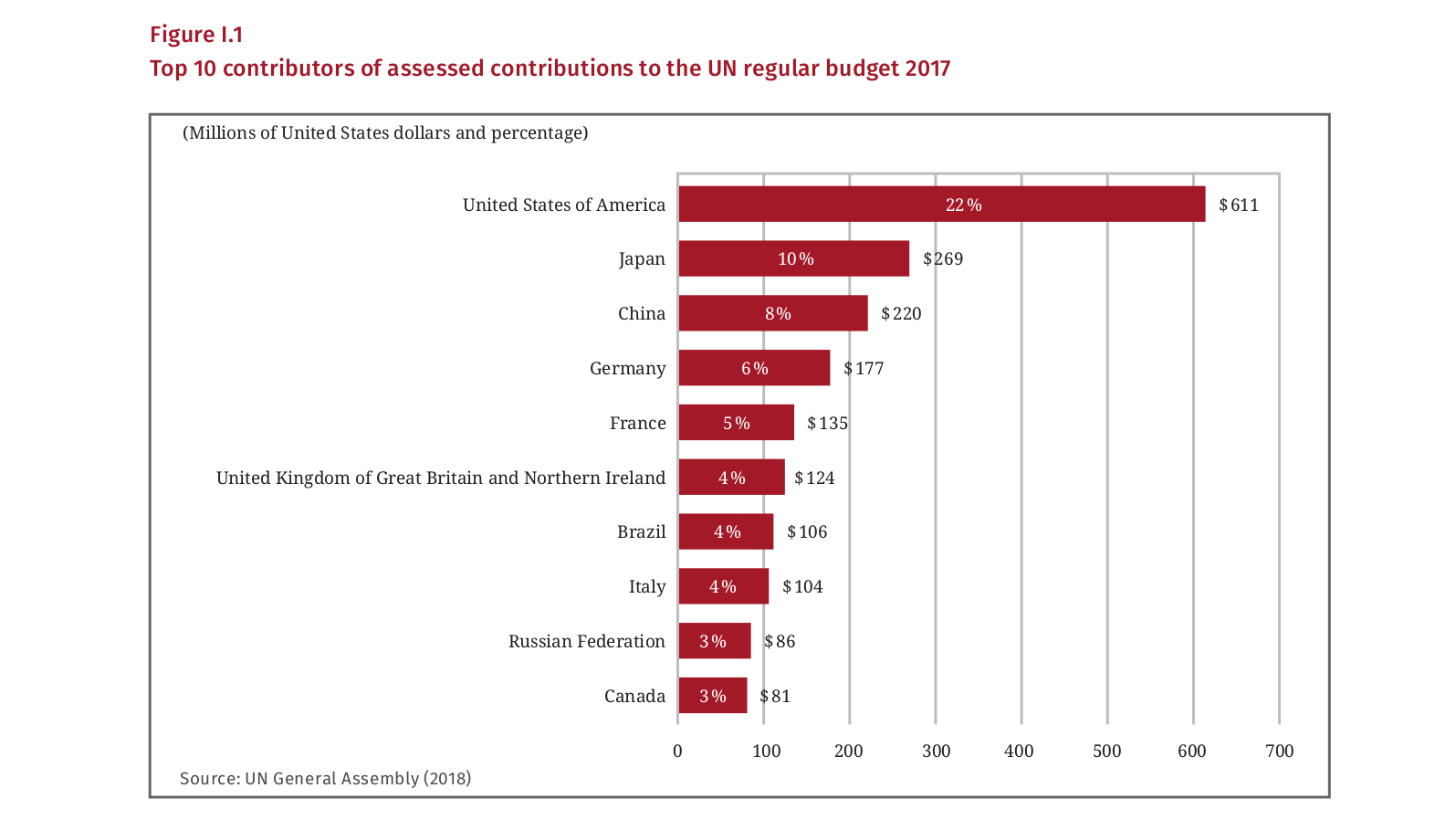

The total assessed contributions to the UN regular budget in 2017 amounted to US$2.8 billion of which the top 10 Member States contributed 68 percent. [fn] UN General Assembly (2018). [/fn]

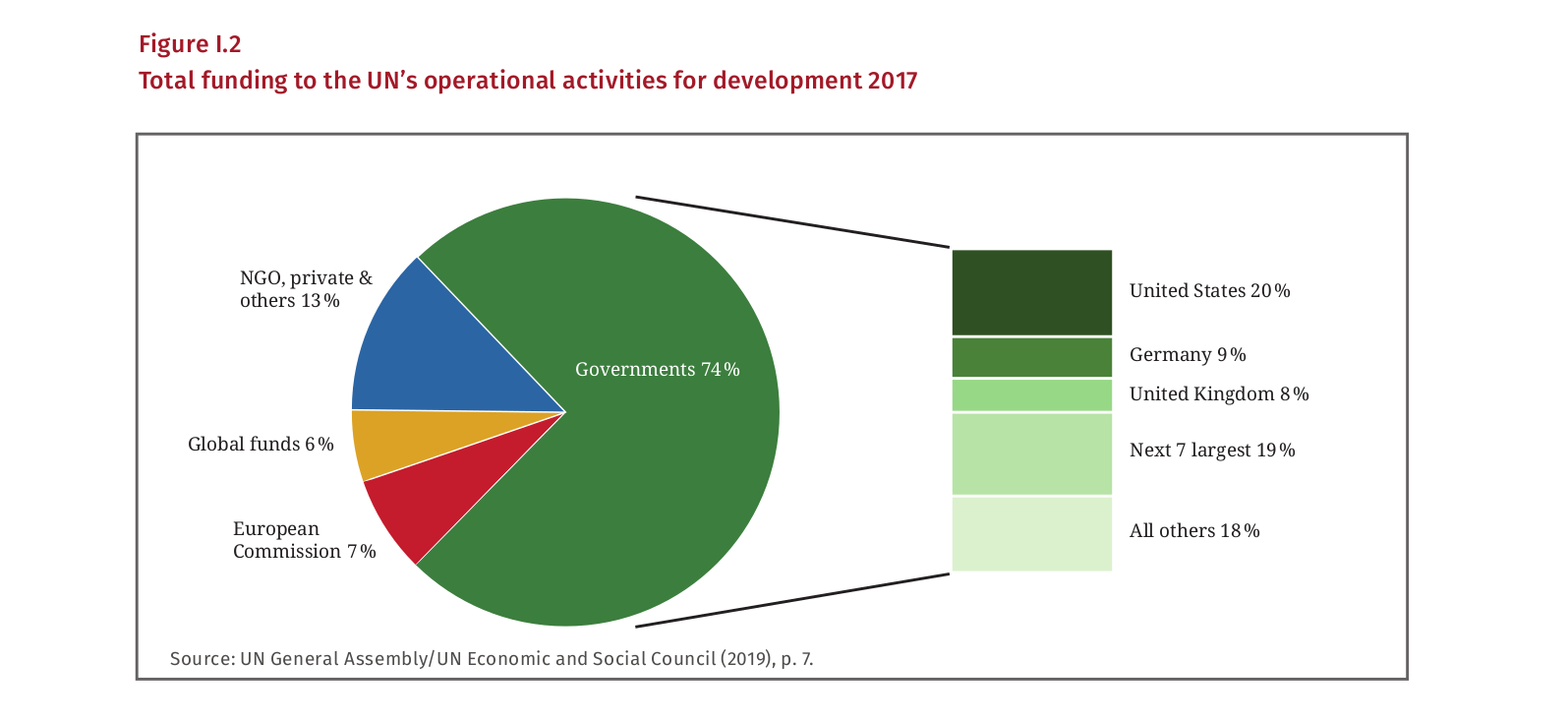

Contributions to the UN’s operational activities for development, which amounted to US$ 33.6 billion in 2017, are also dominated by a few States, with three donors - USA, UK and Germany – accounting for half of all funding from governments (see Figure I.2). [fn] UN General Assembly/UN Economic and Social Council (2019), p. 7. [/fn] Additionally only 20.6 percent of the total supports the core work of the UNDS with the balance mainly earmarked to favour individual donor priorities.

Not only is UN governance vulnerable to undue donor influence but the UN also suffers from inadequate levels of finance. In 2017 it received in total US$ 48.3 billion– the equivalent annually of US$ 7.00 per person on the planet. [fn] UN General Assembly/UN Economic and Social Council (2019). [/fn] By contrast global military expenditures accounted for US$ 1.7 trillion in 2017 and “represented 2.2 percent of global gross domestic product (GDP) or US$ 230 per person”. [fn] SIPRI, 2017, https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2018-05/sipri_fs_1805_milex_2017.pdf. [/fn]

Public investment in the peace architecture of the UN is dwarfed by that in the military infrastructure. Additionally, public finance, supposedly insignificant compared with that of the private sector, subsidized fossil fuels to the tune of US$ 5.3 trillion in 2015. [fn] Coady et al. (2017). [/fn]

The UN funding crisis and pressure from Member States has fueled a turn to the private sector and the philanthropic world, evident in multiple events and partnership initiatives reaching out to the corporate sector, including big data producers, banking and finance and transnational investors.

The SDGs have been marketed as a catalogue for investors. A recent initiative is the Global Investors for Sustainable Development (GISD), a new alliance of Chief Executive Officers to incentivize larger amounts of long-term investment for sustainable development. Inspired by the Swedish Investors for Sustainable Development, this alliance will be officially launched in September 2019 during the UNGA high-level week.

Certainly the sustainable development concept has three essential dimensions – economic, social and environmental – and their integration is essential to achieve the SDGs. However, since its inception the economic dimension has dominated the trio and its policy-making fora has been kept out of the UN sphere of influence. Further integration, without leveling, of the three dimensions will re-enforce the imbalance and make progress hostage to economic policies.

Who governs the economics dimension?

Major dominant economies over decades have successfully kept the UN ‘out of their business’, with steadfast protection of a separate jurisdiction for the Bretton Woods Institutions (BWIs) – the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. This constitutes de facto the exercise of monopoly (or oligopoly) state power that has undermined democratic multilateralism for many decades and has out-ranked the search for economic, social, gender and ecological justice.

The negative impact on the ability of governments to meet their human rights obligations, civil, political, economic, social and cultural, has been documented by a number of UN human rights experts and special rapporteurs.

Furthermore Juan Pablo Bohoshavsky, Independent Expert on human rights of the effects of foreign debt and other related international financial obligations of States, has drawn up guiding principles on human rights impact assessments of economic reforms on the full enjoyment of human rights particularly economic social and cultural rights. [fn] UN Human Rights Council (2018). [/fn] The principles address the human rights obligations of economic actors:

Economic policymaking must be anchored in and guided by substantive and procedural human rights standards, and human rights impact assessments are a crucial process that enables States and other actors to ensure that economic reforms advance, rather than hinder, the enjoyment of human rights by all. [fn] Ibid., p. 1. [/fn]

The scope and purpose of the guiding principles are comprehensive:

Some economic policies, such as fiscal consolidation, structural adjustment/reforms, privatization, deregulation of financial and labour markets and lowering environmental protections standards, can have adverse consequences on the enjoyment of human rights. [fn] Ibid., p. 4, para 1.1. [/fn]

Vitally, the attention to accountability by the principles addresses remedy and reparations.

Principle 21 – Access to justice, accountability and remedies:

States must ensure that access to justice and the right to an effective remedy are guaranteed, through judicial, quasi-judicial, administrative and political mechanism, with regard to actions and omissions in the design and/or implementation of economic reform policies that may undermine human rights.

Commentary 21.1 states further that “The right to an effective remedy includes reparations and guarantees of non-repetition” and 21.2 notes:

A functioning system of national, regional and international human rights accountability mechanisms, including independent and empowered national human rights institutions, is critical…

The principles enumerate the ‘obligations of states, IFIs and private actors’ including with regard to their extraterritorial obligations (see Box I.2).

Box I.2: Guiding principles on human rights impact assessments of economic reforms

Principle 13 – International assistance and cooperation: “States have an obligation to respect and protect the enjoyment of human rights of people outside their borders. This involves avoiding conduct that would foreseeably impair the enjoyment of human rights by persons living beyond their borders, contributing to the creation of an international environment that enables the fulfilment of human rights, as well as conducting assessments of the extraterritorial impacts of laws, policies and practices.”

Principle 14 – External influence and policy space: States, financial institutions and other actors “should not exert undue influence on other States so that they are able to take steps to design and implement economic programmes by using their policy space…”

Principle 15 – obligations of public creditors and donors: “International financial institutions, bilateral lenders and public donors should ensure that the terms of their transactions and their proposals for reform policies and conditionalities for financial support do not undermine the borrower/recipient State’s ability to respect, protect and fulfil its human rights obligations.” Further commentary 15.3 states: “States cannot escape responsibility for actions or the exercise of functions that they have delegated to international institutions or private parties (re blended finance and privatization): delegation cannot be used as an excuse to fail to comply with human rights obligations, in abnegation of the extraterritorial character of these obligations.”

Principle 16 – obligations of private creditors: Commentary 16.2: “In connection with principle 13 and commentary 15.3, host and home States’ obligations to protect human rights, including their exterritorial obligations, require the establishment of adequate safeguards against negative human rights impacts resulting from the conduction of private companies.”

As the UN system and the Secretary-General initiate and move closer to establishing alliances with big investors, big corporations, big tech and big data, signing these principles must be the sine qua non for joining any UN alliance. Furthermore resources to undertake independent monitoring and reporting or certification processes must pass the most rigorous conflict of interest test to ensure these are not another manifestation of SDG washing.

Nor should these initiatives compromise the UN’s role and policy space for domestic resource mobilization by means of global tax reform, halting illicit financial flows, and establishing a debt work-out mechanism.

Trade, investment and finance regimes: for or against SDGs?

The UN Committee on Development Policy held an extraordinary meeting in March 2019 at UN headquarters on the future of development policy in the changing multilateral context. Presentations detailed the contradictions in the development policies followed by dominant economies and the policies they enforce bilaterally and through their decision-making stranglehold in the IMF, the G20 and negotiation of trade and investment regimes.

The Committee highlighted the ways in which trade and investment policies limit domestic policy space: “Unfortunately if you sign bilateral trade and investment agreements or regional agreements with rich countries, then your freedom for action is vastly reduced. So please don't sign any of these.” [fn] Power point presentation, Committee on Development Policy session "The Future of Multilateralism," 12 March 2019, UNHQ. [/fn]

It also pointed out how the limited space available is often not used, drowned in numerous regulations and placed out of reach by administrative hurdles and exorbitant legal fees.

The Committee was unequivocal that: “This system is in crisis and it has caused the inequality crisis and the climate breakdown” and that it is “time for a new multilateralism that puts sustainable development and a just transition as the core goals of a value-driven and rules-based multilateral system.” [fn] Ibid. [/fn]

UN policy space

People still turn to the UN in their desire for peace and justice, as other structures of multilateralism are seen more as deal-making and problem-solving processes or for technical standard setting. It has the mandate and justice machinery to close the gulf between the siloes of development, peace and human rights. Its analysis and experience advance the essentials of addressing root causes and practicing prevention, although minimally applied to slow onset disasters (such as inequalities, social disintegration, climate change) as well as immediate natural disasters and conflict devastation.

The UN has a positive (if declining) reservoir of expectations and goodwill. Yet strategies are lacking especially among small and medium states and some CSOs for a transformative set of rules, institutions and action plans to break out of the current malaise. While vocal about the lack of policy space at the country level, there is an avoidance or self-censorship concerning the constraints on the UN’s policy space by dominance or monopoly politics. Furthermore policy space must be understood to mean increased space for the public sector.

Member States committed themselves to addressing the “disparities of opportunity, wealth and power” in the 2030 Agenda. Responses to power disparities are various - and often in conflict. They range from cynicism to damage control, from “doing the best we can” (protect victims etc.) to the need for systemic change.

The call for new rules often falls short of addressing how to get the dominant to adhere to the rules and even allow them to be written.

One appeal is for ‘win-win’ approaches, seeing partnerships as a strategy for inclusiveness. But this ignores the power imbalance within partnerships and de facto reflects the rules of the dominant, and so risks increasing inequalities rather than inclusion.

It appears as though multi-stakeholderism is another manifestation of neoliberal governance. It labours under the false assumption that ‘stakeholders’ are equal in participation and resources, and ignores the rights of those ’stakeholders’ who rely on democratic governance and governments.

Strategies for addressing power disparities reveal the tensions between those who accept this reality and try to align with the winners or limit the damage, and those who want more fundamental change that reduces and redistributes the power of the dominant.

Among small and medium states from all regions the same tensions and splits are evident – in strategies, in blocs and in perceptions of options: align or regroup.

These tensions are also evident in the UN system and among CSOs. While parts of the UN system promote and propagate partnerships, the OHCHR documents intimidation, recrimination and reprisals, practiced by State and non-State actors. [fn] UN Secretary-General (2018). [/fn]

Some embrace other power centres such as big business/corporations and big NGOs, or those offered by regionalism and South-South Cooperation. This is seen as an incremental and politically feasible approach to breaking down the immense and growing concentration of power. This approach is aligned with strategies to increase policy space at the country level, but often falls short of tackling the policy space deficit in global economic and security governance.

Others argue for another UN chamber of parliamentarians or CSOs. As both of these play a vital role in linking national and global governance, perhaps their impact would be enhanced if incorporated permanently into country delegations to the General Assembly, rather than set aside in a parallel chamber.

Economists, ecologists and human rights advocates alike have signaled the need to address the monopoly power dominating political institutions and governance processes and have drawn attention to the reform the investor-state dispute settlement system as an essential first step.

Governance by states or governance by investors?

In an unusual joint letter to the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) addressing Working Group III (Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) Reform), seven human rights experts addressed the urgency to “remedy the power imbalance between investors and States”, calling for systemic reform in their submission to consideration of the architecture of the ISDS system (see Box I.3). [fn] Deva et al. (2019). [/fn]

Box I.3: Human rights experts speak out on investor power

The following human rights experts signed the joint letter on Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) Reform from 7 March 2019:

Surya Deva, Chair-Rapporteur of the Working Group on the issue of human rights and transnational corporations and other business enterprises

Saad Alfarargi, Special Rapporteur on the right to development

David R. Boyd, Special Rapporteur on the issue of human rights obligations relating to the enjoyment of a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment

Juan Pablo Bohoslavsky, Independent Expert on the effects of foreign debt and other related international financial obligations of States on the full enjoyment of all human rights, particularly economic, social and cultural rights

Victoria Lucia Tauli-Corpuz, Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples

Livingstone Sewanyana, Independent Expert on the promotion of a democratic and equitable international order

Léo Heller, Special Rapporteur on the human rights to safe drinking water and sanitation

Their letter addressed many aspects that go to the heart of the governance: responsibilities of states and their ability and willingness to meet their commitments in the 2030 Agenda.

The signatories pointed out the contradictions and incoherence between human rights law and the rule of law, contradictions of particular concern for the

2030 Agenda and the SDGs, which reaffirm the importance of “an enabling international economic environment, including coherent and mutually supporting world trade, monetary and financial systems, and strengthened and enhanced global economic governance. There is a critical need to fundamentally reform IIAs [international investment agreements] and ISDS, so that they foster international investments that effectively contribute to the realization of all human rights and the SDGs, rather than hindering their achievement.

Principle 9 of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) reminds States to “maintain adequate domestic policy space to meet their human rights obligations when pursuing business-related policy objectives with other States or business enterprises, for instance through investment treaties or contracts”. [fn] UN (2011). [/fn]

Principle 10 further provides that:

States, when acting as members of multilateral institutions … should seek to ensure that those institutions neither restrain the ability of their Member States to meet their duty to protect nor hinder business enterprises from respecting human rights.

Speaking to the urgency of systemic reform of ISDS, the letter of the human rights experts states:

The inherently asymmetric nature of the ISDS system, lack of investors’ human rights obligations, exorbitant costs associated with the ISDS proceedings and extremely high amount of arbitral awards are some of the elements that lead to undue restrictions of States’ fiscal space and undermine their ability to regulate economic activities and to realize economic, social, cultural and environmental rights.

The ISDS system can also negatively impact affected communities’ right to seek effective remedies against investors for project-related human rights abuses. In a number of cases, the ISDS mechanism, or a mere threat of using the ISDS mechanism, has caused regulatory chill and discouraged States from undertaking measures aimed at protection and promotion of human rights. [fn] Deva et al. (2019). [/fn]

In addition to concerns about the standards by which arbitrators and decision-makers are appointed and the cost and duration of ISDS cases, the letter draws attention to two neglected issues: access to remedy and participation of affected third parties. It states that:

if the ISDS mechanism continues to allow investors… a special fast-track path to seek remedies to protect their economic interests, the same pathway should be extended to communities affected by investment-related projects…. This will partly address the systematic asymmetry which we alluded to in the beginning. [fn] Ibid. [/fn]

UN and systematic asymmetry

The details of the letter illuminate the multiple barriers faced by public servants and public sector advocates at all levels of government.

Removing the ability of investors to sue States is the first among equals of measures needed for a new generation of governance. The ISDS and similar rules in investment and trade agreements enshrine systematic asymmetry in the very core of the rule of law.

The more the SDGs are promoted to investors under the rubric that “doing good business is doing good”, the more the UN is buying into the market-based approach and relegating its relevance to big money and not to those left behind.

Rather than being committed to democratic governance, the UN is increasingly being used as a platform for market-based solutions, while maintaining the rhetoric of commitment to “no-one left behind”, which if taken seriously is embedded in a human rights approach.

Does the call to leave no-one behind apply to decision-making, governance and accountability or is it limited to the provision of services? Does this commitment reflect a rights-holder orientation or a consumer/client one?

At the same time that the UN leadership appears to be out-sourcing its accountability responsibilities to civil society, it co-opts them into irrelevant multi-stakeholder platforms that take up very limited resources.

This trajectory is positioning the UN as a caretaker in the face of disasters, human and natural, and abdicating its self-professed prevention mission.

To reject governance with the ‘winners take all’ mindset requires challenging this systematic asymmetry and recognizing that power imbalances cannot be corrected by persuading the most powerful players to share or not use their power.

One of the first themes of a revitalized General Assembly could be to examine the impact on its and the UN system’s work of such investor preferences. This initiative would bring efficiency gains for UN system-wide efforts to achieve the SDGs, being a rare opportunity to go to scale and begin to un-ravel the systematic asymmetry, currently baked in by big powers, public and private.

Barbara Adams is Chair of the Executive Board of Global Policy Forum.

Coady, David/Parry, Ian/Sears, Louis/Shang, Baoping (2017): How Large Are Global Fossil Fuel Subsidies? In: World Development 91, March 2017, pp. 11-27.

www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0305750X16304867

Deva, Surya et al. (2019): Letter to Members of the Working Group III of the UNCITRAL. Geneva (OL ARM 1/2019, 7 March 2019).

www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Development/IEDebt/OL_ARM_07.03.19_1.2019.pdf

UN (2011): Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. Implementing the United Nations “Protect, Respect and Remedy” Framework. New York and Geneva.

www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/GuidingPrinciplesBusinessHR_EN.pdf

UN General Assembly/UN Economic and Social Council (2019): Funding analysis of Operational Activities for Development - Addendum 2, advanced unedited edition”, 18 April 2019. New York (UN Doc. A/74/73 - E/2019/4)

www.un.org/ecosoc/sites/www.un.org.ecosoc/files/files/en/qcpr/SGR2019-Add_2%20-%20Funding%20Analysis%20OAD.pdf

UN General Assembly (2018): Financial report and audited financial statements for the year ended 31 December 2017 and Report of the Board of Auditors Volume 2018. New York.

https://undocs.org/en/A/73/5(VOL.I).

UN General Assembly (2013): Format and organizational aspects of the high-level political forum on sustainable development. New York (UN Doc. A/RES/67/290).

https://undocs.org/en/A/RES/67/290

UN Secretary-General (2018): Cooperation with the United Nations, its representatives and mechanisms in the field of human rights. Report of the Secretary-General. New York (UN Doc. A/HRC/39/41).

https://undocs.org/A/HRC/39/41

UN Human Rights Council (2018): Guiding principles on human rights impact assessments of economic reforms. Report of the Independent Expert on the effects of foreign debt and other related international financial obligations of States on the full enjoyment of human rights, particularly economic, social and cultural rights. Geneva (UN Doc. A/HRC/40/57).

https://undocs.org/A/HRC/40/57

UN Secretary-General (2019a): Implementation of General Assembly resolution 71/243 on the quadrennial comprehensive policy review of operational activities for development of the United Nations system – Advanced, unedited version, 18 April 2019. Report of the Secretary-General. New York (UN Doc. A/74/73 - E/2019/4).

www.un.org/ecosoc/sites/www.un.org.ecosoc/files/files/en/qcpr/SGR2019-%20Advance%20Unedited%20Version%20-%2018%20April.pdf

UN Secretary-General (2019b): Secretary-General remarks to Informal Session of the General Assembly, 16 January 2019. New York.

www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/statement/2019-01-16/secretary-general-remarks-informal-session-of-the-general-assembly-bilingual-delivered

UN Secretary-General (2017): Remarks to the High-level Political Forum on Sustainable Development, 17 July 2017. New York.

www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/speeches/2017-07-17/secretary-generals-high-level-political-forum-remarks