By Jens Martens, Global Policy Forum

Governments and international organizations have responded to the economic and health crises resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic and consequent lockdown on an unprecedented scale. The announced liquidity measures, rescue packages and recovery programmes total US$ 11 trillion worldwide. A total of 196 countries and territories have taken political measures, albeit of very different scale and scope, depending on their fiscal capacity and policy space.

If used in the right way, these programmes could offer the chance to become engines of the urgently needed socio-ecological transformation proclaimed in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Some governments and international organizations have explicitly articulated this claim by promising not to return to the old normal after the dual crisis and to "build back better", for instance by a Green (New) Deal.

But the reality behind these aspirations looks quite different. There are indications that policy responses to the crisis ignore its structural causes, favour the vested interests of influential elites in business and society, further accelerate economic concentration processes, fail to break the vicious circle of indebtedness and austerity policies, and in sum, widen socioeconomic disparities within and between countries. Such responses risk intensifying social conflicts, increasing political instability and distancing the world from achieving the SDGs rather than bringing it closer to these goals.

Worst global economic downturn since the Great Depression

Governments around the world have introduced far-reaching contact and travel restrictions to contain the COVID-19 pandemic and save lives. This brought economic activities in many sectors, from goods production to tourism, to a virtual standstill. The result was the worst global economic downturn since the Great Depression in the 1930s.

In its World Economic Outlook from June 2020, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) predicts a global recession, with the world economy shrinking by an average of 4.9 percent in 2020.[1] At first glance, this number does not appear to be particularly serious, but it is associated with dramatic social and economic consequences: thousands of companies have already had to close their doors, and working-hour losses for the second quarter of 2020 (compared to the last quarter of 2019) are estimated to reach an equivalent to 400 million full-time jobs, according to estimates by the International Labour Organization (ILO).[2] Even worse affected are workers in informal employment, the majority of them women. The ILO estimates that the crisis has affected around 1.6 billion informal workers worldwide. This is particularly devastating in countries that do not have functioning social security systems. These countries are home to 73 percent of the world population.[3] Many of these informal workers have lost any sort of livelihood as a result of the global lockdown.[4] And the crisis is far from over. Experts warn of a ticking time bomb of global insolvencies, which will not peak until 2021. Allianz Research predicts a 35 percent increase in global business insolvencies in 2021 (compared to 2019).[5] It estimates the increase at 40 percent for China, 45 percent for Brazil and as much as 57 percent for the USA. This will result in further job losses and massive negative domino effects along the global supply chain.

Fiscal and monetary crisis response of historic proportions

Governments and central banks have responded to the COVID-19 crisis and the consequences of the lockdown measures in most parts of the world with financial interventions of historic proportions. In the six months between February and July 2020 alone, the fiscal measures announced by governments totaled almost US$ 11 trillion.[6] According to IMF estimates, half of these measures (US$ 5.4 trillion) consisted of additional government spending and foregone revenue, and the other half (US$ 5.4 trillion) consisted of liquidity support, for example, in the form of loans, equity injections, and guarantees. Thus, governments are expected to provide more than three times as much funding as during the last global financial crisis in 2008-2009. McKinsey has calculated that the financial support provided by Western European countries alone, at around US$ 4 trillion, is almost 30 times larger than today's value of the post-World War II Marshall Plan.[7]

And that is not all. To prevent a global financial crash and a credit crunch, central banks in over 90 countries, led by the US Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank (ECB), have provided "first aid", cut interest rates (where still possible) and pumped over US$ 6 trillion in liquidity into the markets.[8] This was achieved through, among other things, the expanded purchase of public securities and, in part, corporate bonds. To this end, the ECB, for instance, in addition to its existing instruments has set up the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP), which alone has a volume of EUR 1,350 billion.[9]

Central banks primarily support national governments, banks and large corporations. In individual cases, however, they also support states and local authorities. The Federal Reserve, for instance, has created the Municipal Liquidity Facility (MLF) to purchase new debt issued by states, cities, and counties, all of which are facing higher spending to fight the pandemic, reduced tax revenue and delayed income tax filing. To support states and large cities, the Federal Reserve announced it would purchase up to US$ 500 billion in new short-term debt issued by states, cities, and counties. But most counties and cities cannot tap into this aid, and those that can will have to repay that debt sooner or later and risk further reducing their ability to provide essential public services.

That is why the Global Task Force of Local and Regional Governments, which coordinates the policy work of major local government networks, demands the acceleration of transformative actions in the aftermath of the COVID-19 outbreak. It states:

As countries and international entities discuss financial packages and funds to recover economies, we call to ensure and reinforce public service provision at all levels as a means to build back better. … We call on international systems and national governments to promote legal and regulatory reforms necessary to enhance municipal and regional governments’ resources and capacity to act and carry out the goals, especially during periods of distress.[10]

But in most countries of the global South neither the central banks nor the governments have the necessary resources and instruments to mitigate the devastating effects of the crisis.

Unequal distribution of financial support

In addition to immediate central bank interventions, two phases can be distinguished in governments' fiscal policy responses to the pandemic:

1. short-term emergency relief to finance the additional costs for health systems and to compensate for the immediate economic losses for private households and companies;

2. longer term reconstruction programmes and stimulus packages to support sustainable economic recovery, promote the necessary structural change and increase resilience to future crises.

A large part of the funds has so far been used for short-term emergency support.

In the USA alone, four major financial packages have been adopted, with a total volume of almost US$ 3 trillion.

COVID-19 emergency relief measures adopted by the US Congress 2020

Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economy Security Act (“CARES Act”): US$ 2.3 trillion

Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act: US$ 483 billion

Families First Coronavirus Response Act: US$ 192 billion

Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act: US$ 8.3 billion

The funds are mainly used to support companies, both small businesses and large corporations, with grants, loans and guarantees to finance healthcare costs (hospitals, virus tests, Medicaid, etc.), to support state and local governments and to provide one-time cash payments and other benefits to individual citizens. In part, these funds are used to fill financial gaps that exist due to the weakness of the US social security system. Many millions of Americans do not have health insurance, do not have access to sick pay and receive very limited unemployment benefits when they are laid off.

Many countries of the global South face similar problems, but they have far less fiscal capacity. Many have tried to prevent the worst consequences of the crisis by means of short-term tax breaks and financial assistance programmes for the most vulnerable. In India, for example, short-term relief measures included in-kind (food, cooking gas) and cash transfers to lower income households, insurance coverage for workers in the healthcare sector and wage support and employment provision to low-wage workers. Egypt increased pensions, Indonesia expanded its social-welfare programme to include food assistance; Brazil provided temporary income support to vulnerable households, including cash transfers to informal and unemployed workers; and Morocco introduced staggered subsistence aid to households of informal workers.[11]

Even so, these measures are far from sufficient to prevent unemployment, poverty and hunger from increasing significantly.

Not only governments but also local authorities are facing major challenges in responding to the social consequences of the crisis. They had to take emergency measures, set-up new services to enable proper lockdown, and contain the spread of the virus in their communities (see Box 2.1).

More than 3.9 billion people - half the world's population – have been affected by the lockdown decisions of their governments in the first half of 2020. But for many of them, the appeals to stay at home, wash hands thoroughly and keep at a six-foot physical distance seem cynical. After all, more than 1 billion people worldwide live in densely populated slums or informal settlements. Many live in cramped conditions and often have no access to the most vital public services such as water, sanitation and electricity. The slums are a perfect breeding ground for viruses. The same is true for the overcrowded refugee camps in countries such as Bangladesh and Greece, where the occupants are forced to live in inhumane conditions.

When the first phase of COVID-19 support measures comes to an end, many cities will be confronted with a massive increase in homelessness, even in richer countries. Many residents who lost their jobs will no longer be able to pay high rents or mortgages. Where there is no adequate legal protection for them, families threaten to be thrown out on the streets overnight. This is a result of the fact that governments have spent many years liberalizing real estate markets, privatizing public property and neglecting social housing. The problem does not only exist in poorer countries. Even in the USA, for instance, 20 to 28 million renters are facing evictions after the temporary eviction moratoriums expire.[12]

Even before COVID-19, many countries of the global South were already in an economic crisis, one characterized by contractionary fiscal policy, growing debt and austerity policy measures that made these countries more vulnerable to future crises. In this context, economists Isabel Ortiz and Matthew Cummins warned that austerity becomes “The New Normal".[13] As a result, most governments face serious fiscal constraints in responding to the current crisis, in part shaped by IMF conditionalities and by their dependence on international financial markets and credit rating agencies and exacerbated by the sharp decrease in public revenues due to the decline in tax payments and export earnings.

It is therefore not surprising that the COVID-19 fiscal responses of the countries of the global South are substantially lower than those of the countries of the global North, not only in absolute terms but also in relation to their GDP.

At the same time, a large part of the fiscal support flows into the business sector. A progress report by the G20 finance ministers on their COVID-19 Action Plan states:

Across G20 advanced economies, financial support for businesses made up the largest share of fiscal measures – equal to 15 percent (approx.) of GDP versus 7.5 percent (approx.) of GDP for non-business support, on average. Among G20 emerging market economies, fiscal interventions were also concentrated in the business sector – equal to 4 percent (approx.) of GDP versus close to 2.5 percent of GDP for non-business support, on average.[14]

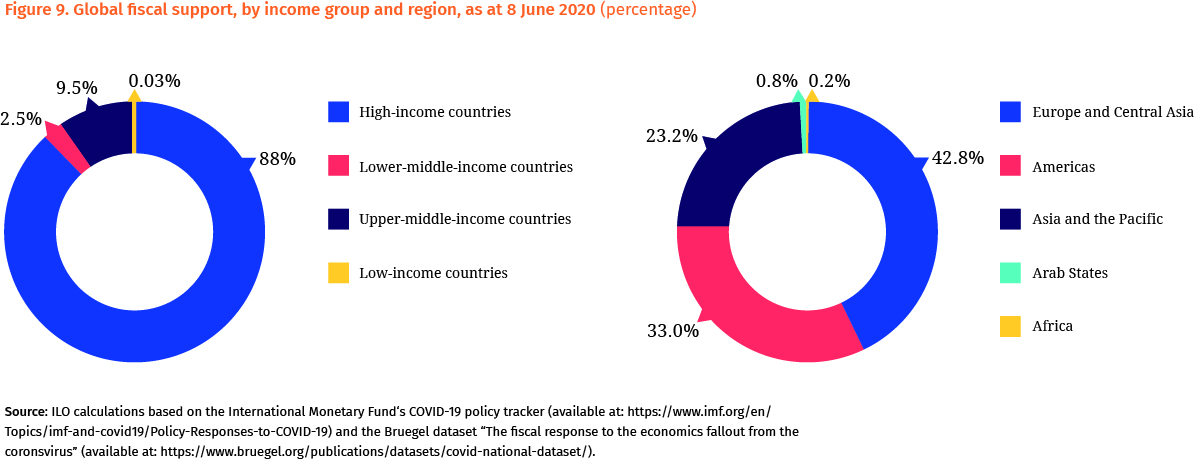

In the poorer countries of the global South the fiscal space is much smaller. The ILO has calculated that 88 percent of global fiscal support is accounted for by high-income countries, but only 0.03 percent by low-income countries (see Figure 2.1.).

Figure 2.1.

Global fiscal support, by income group and region

(as at 8 June 2020, in percent)

Source: ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the World of Work. Fifth edition, 30 June 2020.

Recovery on credit?

Most countries in the world are in a dual emergency situation as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic: on the one hand, their revenues have shrunk dramatically as a result of the economic lockdown and resulting contraction; on the other hand, they had to increase their expenditures in order to prevent a humanitarian disaster and to finance urgently needed relief and reconstruction programmes. To close the funding gap, many are left with the short-term option of taking out new loans. For most countries of the global North, especially the USA and the countries of the EU, this is feasible given low, and in some cases even negative, interest rates. Most countries of the global South do not have this option. They are dependent on international financing through grants and public and private loans.

As early as March 2020, the United Nations called for a US$ 2.5 trillion coronavirus crisis package to counter the catastrophic consequences of the pandemic and a global recession for the countries of the global South. The package comprises three sets of measures:[15]

· US$ 1 trillion should be made available through the expanded use of Special Drawing Rights.

· US$ 1 trillion of debts owed by developing countries should be cancelled in 2020.

· US$ 500 billion needed to fund a Marshall Plan for health recovery and dispersed as grants.

So far, additional grants to address the most pressing problems related to the pandemic have been made available in far smaller amounts than would be necessary. This also applies to the activities of the World Health Organization (WHO) and other organizations of the UN system (see also Table 2.1.):

· The WHO has estimated additional requirements of US$ 1.7 billion to respond to COVID-19 until December 2020 (Strategic Preparedness and Response Plan). These resources should be used to implement priority public health measures in support of countries to prepare and respond to coronavirus outbreaks, as well as to ensure continuation of essential health service. By mid-August 2020, only 50 percent of the requested funds have been received (US$ 872.9 million).[16]

· The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) launched the COVID-19 Global Humanitarian Response Plan (GHRP) in April 2020, to respond to the direct public health and indirect immediate humanitarian consequences of the pandemic, particularly on people in countries already facing other crises. The financing requirements over a period of nine months (April–December 2020) are estimated at US$ 10.3 billion. By mid-August 2020, governments had provided only US$ 2.21 billion (21%).[17]

· The UN launched the system-wide COVID-19 Response and Recovery Fund in April 2020. The financial requirements of the fund are projected at US$2 billion, with US$1 billion needed in the first nine months. The fund is intended to complement the WHO’s Strategic Preparedness and Response Plan and OCHA’s GHRP. By mid-August 2020, The UN had received only US$ 51 million (5% of the amount requested for 2020) from eight donors.[18]

A promising financing option for the countries of the global South would be the issue of additional Special Drawing Rights by the IMF. Such a proposal is supported not only by many economists and IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva, but also by the vast majority of IMF member states. It has so far failed due to the veto of the US government.[19]

Moreover, the debt cancellation measures demanded by the United Nations, governments and many civil society organizations also have not yet been achieved. Between April and July 2020, the IMF only approved debt service relief from its Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust (CCRT) for 28 eligible low-income countries (LICs) for six months, estimated at US$ 251 million.[20] And in April 2020 as well, G20 leaders announced their Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) from May to the end of 2020 for 73 primarily LICs. The G20 initiative covers up to US$ 20 billion of bilateral public debt owed to official creditors but does not apply to the debt owed to private lenders and multilateral creditors. Thus, instead of spending the money saved from debt relief on healthcare and other COVID-19 related activities, it has to be used to pay the private creditors on time and in full. In fact, the G20 initiative prioritizes private over public creditors.

According to a study issued by Oxfam, Christian Aid, Global Justice Now, and the Jubilee Debt Campaign in July 2020, so far 41 countries have applied for debt relief, potentially saving them up to US$ 9 billion in 2020. However, the 73 countries still have to repay up to US$ 33.7 billion in debt relief through the end of the year, and still owe at least US$ 11.6 billion to private creditors, including commercial banks and investment funds, and roughly US$ 13.8 billion to multilateral development banks.[21]

At least there are signs of some progress in Argentina, which has reached a basic agreement with its main private creditors, led by BlackRock Inc, in early August 2020 to restructure US$ 65 billion in foreign debt, allowing Argentina to receive significant debt relief. After the restructuring has been approved by the creditors, Argentina will start talks with the IMF to replace the now-defunct US$ 57 billion loan programme negotiated by the previous administration two years ago. The debt crisis and the adjustment measures imposed by the IMF have led to a massive increase in poverty in Argentina. It remains to be seen if the new agreements with private creditors and the IMF can turn this trend around.

For many countries of the global South, the only remaining main option for financing the most urgent COVID-19 relief and recovery programmes is to obtain new loans from multilateral development banks and the IMF. The World Bank has pledged to make available US$ 160 billion over a 15-month period to help developing countries respond to the health, social and economic impacts of COVID-19;[22] the newly established funds of the various regional development banks amount to US$ 73.8 billion; and, according to IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva, “the IMF has secured $1 trillion in lending capacity, serving our members and responding fast to an unprecedented number of emergency financing requests—from over 90 countries so far”[23] (see Table 2.1).

|

Table 2.1. International funding mechanisms for COVID-19 response The following table summarizes selected funding mechanisms in the UN system, multilateral development banks and other financial institutions (as of June 2020). It is not intended to be exhaustive. The numbers reflect the projected funding, not the real disbursements. The vast majority of the funds are repayable loans. |

|||

|

Organization |

Fund |

Projected amount (US $) |

Further information |

|

UN OCHA |

10.3 bn |

https://www.who.int/health-cluster/news-and-events/news/GHRP-revision-july-2020/en/ |

|

|

UN System |

2 bn |

https://unsdg.un.org/sites/default/files/2020-03/SG-Response-and-Recovery-Fund-Fact-sheet.pdf |

|

|

WHO |

COVID-19 Strategic Preparedness and Response Plan |

1.74 bn |

https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/donors-and-partners/funding |

|

|

|||

|

IMF |

1,000 bn |

||

|

World Bank Group |

160 bn |

||

|

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) |

Solidarity Package |

21 bn |

|

|

Asian Development Bank (ADB) |

20 bn |

||

|

Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) |

COVID-19 Crisis Recovery Facility |

10 bn |

|

|

African Development Bank (AfDB) |

COVID-19 Response Facility |

10 bn |

|

|

New Development Bank |

COVID-19 Emergency Programmes |

4 bn |

https://www.ndb.int/projects/list-of-all-projects/approved-projects/ |

|

Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) |

2.8 bn |

||

|

Development Bank of Latin America (CAF) |

Regional Emergency Credit Line |

2.5 bn |

|

|

Islamic Development Bank Group (IsDBG) |

Strategic Preparedness and Response Programme |

2.3 bn |

|

|

OPEC Fund for International Development |

1 bn |

||

However, the financing of COVID-19 relief and recovery programmes through the increase in foreign debt and the reliance on IMF support is problematic, mainly for two reasons.

First, many countries had already reached the limits of their debt sustainability before the COVID-19 pandemic. The foreign debt of the countries of the global South had risen to all-time high. Public and private debt of developing and emerging countries totaled US$ 9.7 trillion in 2018.[24] They are thus now more than twice as high as at the peak of the last global financial crisis in 2009 (US$ 4.5 trillion) and more than four times as high as in 2000.

In 2018, US$ 1,239 billion in debt service payments flowed from these countries to foreign creditors[25] - more than eight times as much as the OECD countries provided this year in official development assistance (ODA) (US$ 153 billion).[26] As a result of the COVID-19 crisis, falling commodity prices, dwindling foreign reserves and weakening currencies have made it now even harder for many countries to meet external debt payments.

According to the IMF, the number of low-income countries, which are either in debt distress (8) or at high risk of debt distress (28), has doubled in the last five years from 18 to 36.[27] For them, a further increase in debt is not a viable option.

Back to the old normal?

In addition, the use of IMF funds may let the fox guard the henhouse. Already in the Ebola crisis in 2015, the IMF was criticized for its harsh conditionalities, which had weakened the health systems of affected countries and thus fostered the spread of the disease.[28] More recent analysis by ActionAid and Public Services International (PSI) revealed how IMF conditionalities restricted critical public employment in the lead-up to the COVID-19 crisis. Of the 57 countries last identified by the WHO as facing critical health worker shortages, the IMF advised 24 -- among them Burkina Faso, Liberia and Mozambique -- to cut or freeze public sector wages.[29]

Confronted with the disastrous consequences of weakened health systems, it was hoped that the IMF and the World Bank would learn lessons from past mistakes and realize that their austerity policy prescriptions were not exactly in line with the assertions of "building back better" and "sustainable recovery". But statements from the Fund and the Bank, and an analysis of the IMF's recent lending programmes, suggest that they see the current crisis as merely a brief interruption on the way back to the old normal of contractionary fiscal policy and unwavering confidence in the private sector.

The World Bank makes it very clear in its PPP blog that “healthy cooperation with the private sector will be more important than ever as countries exit this crisis even more fiscally constrained”.[30]

And the IMF states in its Fiscal Monitor of April 2020, that “once the current economic situation improves, a more ambitious, credible medium-term fiscal consolidation path is needed to bring debt and interest expenditure down” in emerging and middle-income economies.[31]

In the Summer 2020 edition of its Bretton Woods Observer, the Bretton Woods Project presented ample evidence that the IMF is continuing its conventional austerity policy course in its lending decisions.[32] Examples include:

· In June 2020, the IMF agreed a 12-month, US$ 5.2 billion loan programme with Egypt. It detailed a FY2020-2021 primary budget surplus target of 0.5 percent to allow for COVID-19-related spending, but demanded it be restored to the pre-crisis primary surplus of 2 percent in FY2021-2022;[33]

· In Ukraine, the IMF approved a new 18-month, US$ 5 billion loan programme in June 2020. It praised Ukraine’s fiscal consolidation efforts pre-COVID-19 that were “achieved mainly through a reduction in the real value of wages and social benefits”,[34] and set out a fiscal consolidation plan targeting a primary surplus of about 1-1.5 percent by 2023.

· In Jordan, on top of a four-year loan programme agreed in January 2020, the IMF provided urgent support in May 2020 under its Rapid Financing Instrument (RFI). While the Fund recognized the need to reconsider fiscal consolidation targets for 2020 in the context of COVID-19 spending, it noted that the authorities plan to resume the “needed fiscal consolidation from 2021 by [inter alia] cutting lower priority spending”.[35]

· In Pakistan, long-term fiscal consolidation measures were agreed in an IMF US$ 1.386 billion loan programme in April 2020.[36] It complements a programme from July 2019 which, according to the IMF “includes improved plans for social protection measures. Over the medium term—the next three to five years-- there will be more jobs, better health care and improvements in education.”[37] However, in response to this programme public protests against hospital privatizations and a salary freeze for government employees were reported in March and June 2020.

· In Ecuador, the impact of COVID-19 is one of the most devastating in the world, severely exacerbated by six years of IMF-backed fiscal austerity measures that resulted in a 64 percent decrease in public investment in the health sector in just the last two years. Yet, even now, Ecuador is undergoing IMF-mandated structural reforms that further dismantle its health system (see Box 2.2).

Aligning COVID-19 responses with human rights and the SDGs

Especially in times of crisis, the human rights obligations of governments mandated by the United Nations human rights agreements and the 2030 Agenda should not be undermined by conditions imposed by foreign donors or creditors, in particular the IMF. Therefore, all austerity policy measures must be put to the test. The Guiding Principles on Human Rights Impact Assessments of Economic Reforms, presented in December 2018 by Juan Pablo Bohoslavsky, then UN Independent Expert on External Debt and Human Rights, could play an important role in this regard. Adopted on 21 March 2019, Human Rights Council resolution 40/8, “took note with appreciation” of the Guiding Principles encouraging Governments, relevant UN bodies, specialized agencies, funds and programmes and other intergovernmental organizations “to consider taking into account the guiding principles in the formulation and implementation of their economic reform policies and measures”.[38]

Especially now in the midst of the COVID-19 crisis, the Guiding Principles can thus serve as a tool for checking whether economic policy measures are in line with international human rights obligations.

But needed transformation cannot only be about damage control of economic and financial policy decisions. Rather, the resources of the COVID-19 reconstruction and economic stimulus packages should be used proactively to promote human rights and the implementation of SDGs.

UN Secretary-General António Guterres affirmed that human rights can and must guide COVID-19 response and recovery. The recovery measures must also respect the rights of future generations, enhancing climate action aiming at carbon neutrality by 2050 and protecting biodiversity. “We will need to ‘build back better’ and maintain the momentum of international cooperation, with human rights at the centre”, he said in April 2020.[39]

UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Executive Secretary Patricia Espinosa said along the same lines: “With this restart, a window of hope and opportunity opens… an opportunity for nations to green their recovery packages and shape the 21st century economy in ways that are clean, green, healthy, safe and more resilient.”[40]

And even IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva called for a green recovery and stated: “From a position nearing economic stasis there is nonetheless an opportunity to use policies to reshape how we live and to build a world that is greener, smarter, and fairer.”[41]

For governments this would mean, for example, bringing their COVID-19 programmes in line with national sustainable development strategies and human rights. So far, this has not been done systematically. In South Africa, for example, economic and monetary policies are still seen to be outside the purview of rights and are entrenching rather than divisive pre-existing inequalities (see Box 2.3).

In the first phase, many of the governments' COVID-19 emergency programmes contained certain social components that aimed to provide (more or less targeted) support for families in need, prevent unemployment and keep small businesses and companies financially afloat. But aside from the fact that even these huge amounts of money could not prevent the global rise in unemployment, poverty, and corporate bankruptcies, the temporary measures produced at best a flash in the pan effect that will quickly evaporate when the support ends. The social catastrophe then comes only with a delay. It can only be prevented if the short-term support leads to fundamental structural changes, such as the strengthening of the public social security systems and improved remuneration and rights of workers in the care economy.

Environmental considerations, on the other hand, played hardly any role in the first phase of COVID-19 relief programmes; they slipped down the priority list of many governments.

Of course, the closure of entire sectors of the economy in spring 2020 naturally resulted in less greenhouse gas emissions. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), global CO2 emissions from fossil fuels will decrease by 8 percent in 2020.[42] However, greenhouse gas reductions will be short-lived.[43] When air and vehicular traffic and manufacturing production resume, emissions might even increase faster than predicted before the crisis because necessary innovation and transformation processes have been stopped or slowed down, not least as a result of intense lobbying of corporate interest groups.[44]

Many economic relief packages are ecologically blind. In the world's largest legislative project, the US Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economy Security Act ("CARES Act"), for example, terms such as “climate change” or “sustainability” do not appear once in its 880 pages.[45] In contrast, the aviation industry and other businesses deemed "critical to maintaining national security" received government grants and loans in the high double-digit billions.[46]

European airlines have sought an unprecedented EUR 34.4 billion (as of 26 June 2020) in government bailouts since the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis, most of them without binding environmental conditions.[47] To be sure, there are a few exceptions: in June 2020, the Austrian government agreed on a EUR 450 million bailout deal for Austrian Airlines, conditioned on restricting short-distance flights, banning cheap tickets below EUR 40, including a EUR 12 environmental tax to each ticket, and halving its CO2 emissions by 2030.[48]

Overall, however, the first phase of COVID-19 responses did not succeed in recognizing the demand of many CSOs and trade unions that access to corporate bailouts and other public funds should be subject to conditions designed to protect and empower workers, stop tax dodging and end the corporate practices fueling inequality, climate breakdown and human rights abuse.[49]

It would therefore be all the more important that now, in the second phase of the political responses to the COVID-19 crisis, longer-term economic stimulus packages not only support the economic recovery, but also promote necessary structural change. After all, some stimulus packages explicitly claim to "reconcile" climate action and economic recovery.

In Germany, for instance, a EUR 130 billion stimulus package adopted in June 2020 comprises a temporary VAT reduction, income support for families, grants for small and medium enterprises (SMEs), financial support for local governments, and subsidies/investment in green energy and digitalization. But it also contains expanded credit guarantees for exporters and export-financing banks, thus signaling that the German Federal Government will not abandon the conventional export-based growth model.

In July 2020, the European Council agreed on the Next Generation EU recovery fund, which aims to provide EUR 750 billion in total to EU member states (split between EUR 390 billion grants and EUR 360 billion loans).[50] Overall, 30 percent of the fund will be targeted towards climate change related spending.

However, the criteria for what is "climate change-related" remain vague, and the promotion of fossil fuels and nuclear energy is not stopped, nor are climate-damaging transport projects and subsidies for industrial agriculture and factory farming. At the same time, the funds pledged to boost innovative investments or to mitigate the social impact of structural change (e.g., the European Commission’s Just Transition Fund which is supposed to support regions which need to phase out production and use of coal, lignite, peat and oil shale, or transform carbon-intensive industries) have declined significantly.

Finally, the EU is far from fulfilling its global responsibility with regard to funds for international cooperation. Instead, it is continuing its policy of restricting support to refugees, asylum seekers and migrants.

And despite all its public talk about global solidarity in the fight against the coronavirus, in reality the EU seems to join the global race for access to the vaccine (with the USA, Russia and China) by making its own deals with pharmaceutical companies like Sanofi-GSK for purchase guarantees and delivery quantities.[51]

However, the European Commission also affirms that it is

ready to explore with international partners if a significant number of countries would agree to pool resources for jointly reserving future vaccines from companies for themselves as well as for low and middle-income countries at the same time. The high-income countries could act as an inclusive international buyers' group, thus accelerating the development of safe and effective vaccines and maximum access to them for all who need it across the world.[52]

But this statement is very vague and the EU must first prove that it is serious.

There is still time to correct the current reconstruction and stimulus packages and to demand that politicians put human rights and the goals and principles of the 2030 Agenda at the centre of their programmes.

Economists Carilee Osborne and Pamela Choga from the South African Institute for Economic Justice put it very well when they concluded that the social and economic consequences of COVID-19 are not an exogenous shock to an otherwise functioning system, but the consequences of a system that has instability and inequality hardwired into its DNA. Failure to correct this will make the world emerge from the crisis even more unequal, unstable and less sustainable than it was before.

[1] IMF, World Economic Outlook Update, June 2020.

[2] ILO, ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the world of work. Fifth edition, 30 June 2020.

[3] https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/social-security/lang--en/index.htm

[4] https://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_743036/lang--en/index.htm

[5] Allianz Research, “Calm before the Storm: COVID-19 and the Business Insolvency Time Bomb,” 2020.

[6] https://www.imf.org/en/About/FAQ/imf-response-to-covid-19

[7] McKinsey & Company, “The $10 trillion rescue: How governments can deliver impact,” 2020, p. 2.

[8] https://www.imf.org/en/About/FAQ/imf-response-to-covid-19

[9] https://www.ecb.europa.eu/mopo/implement/pepp/html/index.en.html

[10] Global Task Force of Local and Regional Governments (2020): Towards the Localization od the SDGs (https://www.global-taskforce.org/sites/default/files/2020-07/Towards%20the%20Localization%20of%20the%20SDGs.pdf), p. 9.

[11] https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-and-covid19/Policy-Responses-to-COVID-19

[12] According to Emily Benfer, co-creator of the COVID-19 Housing Policy Scorecard with the Eviction Lab at Princeton University (https://evictionlab.org/).

[13] I. Ortiz and M. Cummins, “Austerity, the New Normal, InterPress Service, 2019, http://www.ipsnews.net/2019/10/austerity-new-normal/ and “The Insanity of Austerity”, https://www.project-syndicate.org/onpoint/the-insanity-of-austerity-by-isabel-ortiz-and-matthew-cummins-2019-10?barrier=accesspaylog

[14] Communiqué. G20 Finance Ministers & Central Bank Governors Meeting, 18 July 2020. Annex I: Action Plan Progress Report, p. 8.

[15] https://unctad.org/en/pages/newsdetails.aspx?OriginalVersionID=2315

[16] https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/donors-and-partners/funding

[17] https://fts.unocha.org/appeals/952/summary

[18] http://mptf.undp.org/factsheet/fund/COV00

[19] https://cepr.net/report/the-world-economy-needs-a-stimulus-imf-special-drawing-rights-are-critical-to-containing-the-pandemic-and-boosting-the-world-economy/

[20] https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-and-covid19/COVID-Lending-Tracker#CCRT

[21] Christian Aid/Global Justice Now/Jubilee Debt Campaign/Oxfam, “Passing the buck on debt relief”, 2020, https://oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/10546/621026/mb-passing-buck-debt-relief-private-sector-160720-en.pdf?sequence=4&isAllowed=y)

[22] https://www.worldbank.org/en/who-we-are/news/coronavirus-covid19

[23] https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-and-covid19

[24] “External debt sustainability and development.” Report of the Secretary-General. New York, 2020 (A/74/234), https://undocs.org/en/A/74/234, p. 4.

[25] Ibid., p. 17.

[26] https://www.oecd.org/newsroom/development-aid-drops-in-2018-especially-to-neediest-countries.htm

[27] https://www.imf.org/external/Pubs/ft/dsa/DSAlist.pdf (as of 30 June 2020).

[28] https://www.brettonwoodsproject.org/2015/02/imfs-role-ebola-outbreak/

[29] https://actionaid.org/news/2020/covid-19-crisis-imf-told-countries-facing-critical-health-worker-shortages-cut-public

[30] https://pppknowledgelab.org/ppp-community-forum/news/how-world-bank-looking-covid-19-and-public-private-partnerships-right-now

[31] IMF Fiscal Monitor, “Policies to Support People During the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Washington, D.C., April 2020, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/FM/Issues/2020/04/06/fiscal-monitor-april-2020

[32] Bretton Woods Project, “The IMF and World Bank-led Covid-19 recovery: ‘Building back better’ or locking in broken policies?” In Bretton Woods Observer, Summer 2020, https://www.brettonwoodsproject.org/2020/07/the-imf-and-world-bank-led-covid-19-recovery-building-back-better-or-locking-in-broken-policies/.

[33] https://www.imf.org/en/About/Factsheets/Sheets/2016/08/01/20/33/Stand-By-Arrangement

[34] https://www.imf.org/~/media/Files/Publications/CR/2020/English/1UKREA2020001.ashx, p. 7.

[35] https://www.imf.org/~/media/Files/Publications/CR/2020/English/1JOREA2020002.ashx, p. 8.

[36] https://www.imf.org/~/media/Files/Publications/CR/2020/English/1PAKEA2020001.ashx

[37] https://www.imf.org/en/Countries/PAK/FAQ#Q9

[38] https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Development/IEDebt/Pages/DebtAndimpactassessments.aspx

[39] https://www.un.org/en/un-coronavirus-communications-team/un-urges-countries-%E2%80%98build-back-better%E2%80%99

[40] Ibid.

[41] https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2020/06/turning-crisis-into-opportunity-kristalina-georgieva.htm

[42] https://www.iea.org/reports/global-energy-review-2020/global-energy-and-co2-emissions-in-2020

[43] https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/04/1062332

[44] https://corporateeurope.org/en/2020/04/coronawash-alert

[45] https://files.taxfoundation.org/20200325223111/FINAL-FINAL-CARES-ACT.pdf

[46] See the comprehensive information provided by the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, https://www.covidmoneytracker.org.

[47] https://www.transportenvironment.org/what-we-do/flying-and-climate-change/bailout-tracker

[48] https://uk.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-lufthansa-austrian/lufthansas-austrian-arm-gets-450-million-euro-government-bailout-idUKKBN23F1EN

[49] See https://www.business-humanrights.org/sites/default/files/documents/CESR%20Brief%205%20FINAL%20ADJUST_%20%28002%29.pdf

[50] The European Parliament and national parliaments still need to ratify the agreement in order for the EU to issue the debt to finance the Next Generation EU recovery fund.

[51] https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_1439

[52] Ibid.